Last weekend, I started watching the latest season of Drive to Survive, the Netflix documentary that offers a backstage pass into the lives of the people behind Formula 1, the most popular motorsport in the world. I absolutely loved season 1. In fact, it was what had me fall in love with the sport. It showcased the human stories involved in the Formula 1 circus and the complex web of systems that work to get two working- and preferably point-scoring - cars on the grid. I found it to be a fascinating exploration of high performance, inadvertently showcasing the impact of different leadership styles, decisions and strategies.

What I loved most of all was the storytelling.

And what do I dislike the most about the latest season? The storytelling. The difference is the way the stories are being told. In season 1, it was as if the production team sat down and watched hours upon hours of footage until the stories popped out for them. The lived experiences led to the seamless storytelling of season 1.

In season 5, it's as if the stories were predetermined, and everything was shot with a particular 'angle' in mind. Like in episode 7, which covers Sergio "Checo" Pérez's journey during the Monaco Grand Prix. I'm convinced every driver was asked the same leading question: "what do you think of the rain in Monaco?" because the episode shows 5 different drivers saying a version of "driving in the rain in Monaco is hard." It's not that what they're capturing is incorrect (as someone who hates driving in London because of the angry drivers, I can testify that driving in the rain around the Monaco track at 200mph does look hard!) But that's precisely it. It's unimaginative, unsurprising and feels somewhat contrived. Even though it’s based on reality, it's as if the whole episode has been filmed and filtered to support that one story. One narrow and limited version of reality. And whilst I'm sure this approach probably saves a lot of money and time in post-production, the results are, well, a little bit meh...

Story first. Life second.

As many of you know, I am passionate about the power of storytelling in everyday life. I believe storytelling can be a powerful tool for reimagining ourselves in the world. For example, I've spent a long time trying (and failing) to create a regular meditation habit. I found it much harder to change my reality until I shifted the story I was telling myself. So, instead of being someone "who wants to mediate," I now wake up every morning and tell myself," I am a person who meditates." This simple shift has made meditation a part of my identity. It's not something over there that feels unachievable and secondary to who I am. It's a part of me that has helped me build- and keep- a regular morning meditation habit. To use the words of James Clear, author of Atomic Habits:

"True behaviour change is identity change. When your behaviour and your identity are aligned, you are no longer pursuing change. You are simply acting like the type of person you already believe yourself to be."

This way of utilising storytelling offers us more agency over our lives: the stories we tell ourselves now will impact how we experience our lives. Put simply: the story comes first. I have learnt so much from this principle having replaced some unhelpful stories with life-affirming narratives. Like for example, with a gratitude attitude. Gratitude is like a muscle; the more we work it, the more we feel grateful. So every evening before going to sleep, my husband and I will share 3 things we're grateful for (they can be tiny!) Just looking for something to be grateful for will change the neurochemistry in your brain and train you to look at life through a gratitude lens. The more you do this, the more the world feels like a 'glass half full.' Such a simple story can profoundly impact one's experience of a day.

Yet, I wonder if the stories we create- consciously or not- might limit our ability to relate to life's spectrum of experiences. Stories are like lenses we look through that pre-emptively filter how we see the world. Yet, if we pulled back the stories and were left with the bare experiences, the sense data, would we be able to imagine beyond the limits of the stories we tell ourselves? To open ourselves to a new level of surprise, spontaneity and creative freedom?

Where is your locus of control?

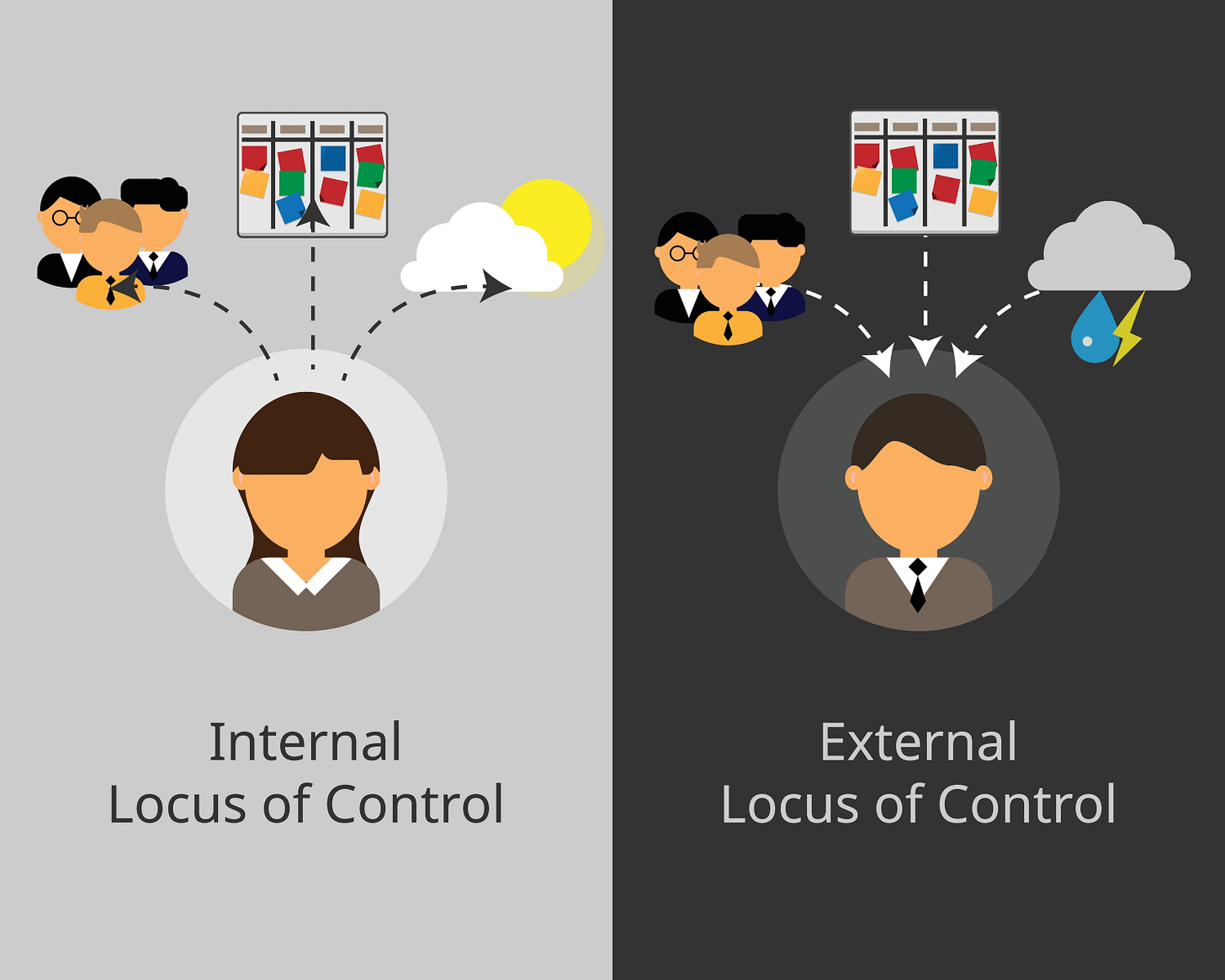

Understanding our locus of control can help us better understand what kind of storyteller we are. The concept was originally developed by Julian Rotter in the 1950s and is understood as a "malleable personality trait" that shapes one's life experience. If we have a more robust internal locus of control, we believe we control our lives and take responsibility for our actions. Beliefs for internal locus of control include: "I am in charge of my destiny" and "I make things happen." In contrast, if we have a stronger external locus of control, we believe those external factors create our circumstances. Beliefs for external locus control include: "what will be will be" & "there’s nothing I can do to change this."

The storyteller in me has always been biased towards the internal locus of control. This approach empowers us to feel that we are "happening" to the world instead of the world "happening" to us. And whilst research confirms that this approach can be game-changing in terms of mental health (over 60 years of research has demonstrated that people who have an internal locus of control are happier and accomplish more in their lives, whereas having an external locus of control has been linked to depression), I wonder if individualism causes us to over-compensate in favour of an internal locus of control. Whilst a self-authoring attitude is proactive, it appears to view life more like a scripted play than one long improvisation. Life is a dance, not a one-way street. And as opposed to thinking in binary terms (internal vs. external), I wonder if it might be more helpful to think of storytelling for what it is: a relationship.

It's a two-way street

Like any relationship, storytelling is a two-way street. And it's a bit of a chicken/egg situation. Do we tell the story first? Or does the story reveal itself to us? I'd argue that great stories need to balance both. There's input and output from both sides. Our stories shape our reality, but our reality shapes our stories. So how can we hold both without narrowing our frame of reference around a single story?

In her 2009 TED talk Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie discusses the dangers of a single story. She speaks about the negative stories and stereotypes that followed her as a Nigerian woman studying in the USA: "my roommate had a single story of Africa: a single story of catastrophe. In this single story, there was no possibility of Africans being similar to her in any way, no possibility of feelings more complex than pity, no possibility of a connection as human equals." I've watched this talk many times, and every time Adichie's closing statement strikes a chord:

"When we reject the single story, when we realise that there is never a single story about any place, we regain a kind of paradise."

This kind of "paradise" for storytelling fills me with wonder and surprise. It's not a predictable and inevitable tale that generalises and limits our experience. It's a presence that processes sense data as it unfolds, not through a fixed agenda but from a creative, spontaneous arising that remains open to surprise.

For the past few years, I’ve felt tired of the contrived and formulaic writing I found on social media and major news sources. So when I stumbled across Substack at the end of last year, I was thrilled to connect with a range of writers, journalists and researchers who stay with the story as it unfolds. Instead of writing with an end in mind, they take you on a journey, a style of storytelling that feels much more genuine, unaffected and more reflective of life itself.

So back to Drive to Survive. Whilst I wish the documentary could bring more life back into the stories it showcases, I’m also questioning whether I am tired of the narrow stories that Formula 1 can tell. Even though the sport is on the cutting edge of research and innovation, it’s surprisingly outdated regarding diversity. In 2020, 88% of all F1 employees were male, and 91% were white. Sir Lewis Hamilton, the only black driver in the history of F1, understands the institutional barriers in place and formed The Hamilton Commission to address the underrepresentation of Black people in the sport. As Claudia George writes for Fourth Wall:

"Sir Lewis has had to overcome enormous hurdles to enter the sport from a working-class background, to become the most talented, successful driver of all time [...] He is doing all he can to facilitate women, people of colour, and people from lower socioeconomic classes to enter the sport, but it is high time the sport did more to help him push this important message."

It seems that Formula 1 is still in many ways, an elitist boys club. It's a tired tale. It would be refreshing to see the sport empower and champion people outside the "billionaire boys club" by creating access not only for the rich but also for people from more humble origins.

Hamilton's story is the stuff of fiction. From growing up in a working-class family with his dad working up to 4 jobs at a time to support his karting dream, he went on to become the 7-time world champion and is considered one of the greatest F1 drivers of all time. Yet, in an interview with the Spanish publication AS, Hamilton said, "If I were to start over from a working-class family, it would be impossible for me to be here today because the other boys would have a lot more money." Born a decade later, would Hamilton's story have been possible? Are the institutional roadblocks simply too big for another ‘Hamilton’ to break through?

A mirror

Whilst storytelling is a relationship, our stories also mirror our relationship with life. Great stories don't sell a single story or binary thinking; they reveal the messiness of the human experience that can't be neatly categorised or defined. To use the words of Sylvia Plath:

"Everything in life is writable about if you have the outgoing guts to do it, and the imagination to improvise."

Instead of looking at our lives through culturally conditioned stories, what if we allowed a little more of the canvas to influence the art? So that the disorderly dance of life can unfold on the page in real-time. It's a more complicated and risky approach, but it feels so much more alive...